This talk was given at a commemoration march in Busselton on 22 February 2025

‘I begin today by acknowledging the Wardandi people, Traditional Custodians of the land on which we gather today, and pay my respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. I recognise that Wardandi people have an ongoing connection to the land and waters of this beautiful place from time immemorial, and acknowledge that they never ceded sovereignty. I extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples here today.’

The information in this speech today comes from depositions written by Captain John Molloy, John Garrett Bussell, Vernon Bussell and Alfred Pickmore Bussell. These depositions are stored at the State Records Office, in the State Library of WA, and describe three punitive settler parties that went out after Wardandi leader Gaywal speared and killed settler George Layman at Wonnerup after an argument on 22 February 1841.[1] These depositions depict the events following George Layman’s death, but also highlight information on a Wardandi man called Bun-ni. This is probably his true Wardandi name, as it has been noted in the records of Charles Symmons, a ‘Protector of Aborigines’ from 1839 to 1857. Symmons’ records generally noted the real name of the Noongar people he interacted with, and he would write their names down phonetically. He spelled Bun-ni’s name as it is written here and this is what I will call him throughout this talk.[2]

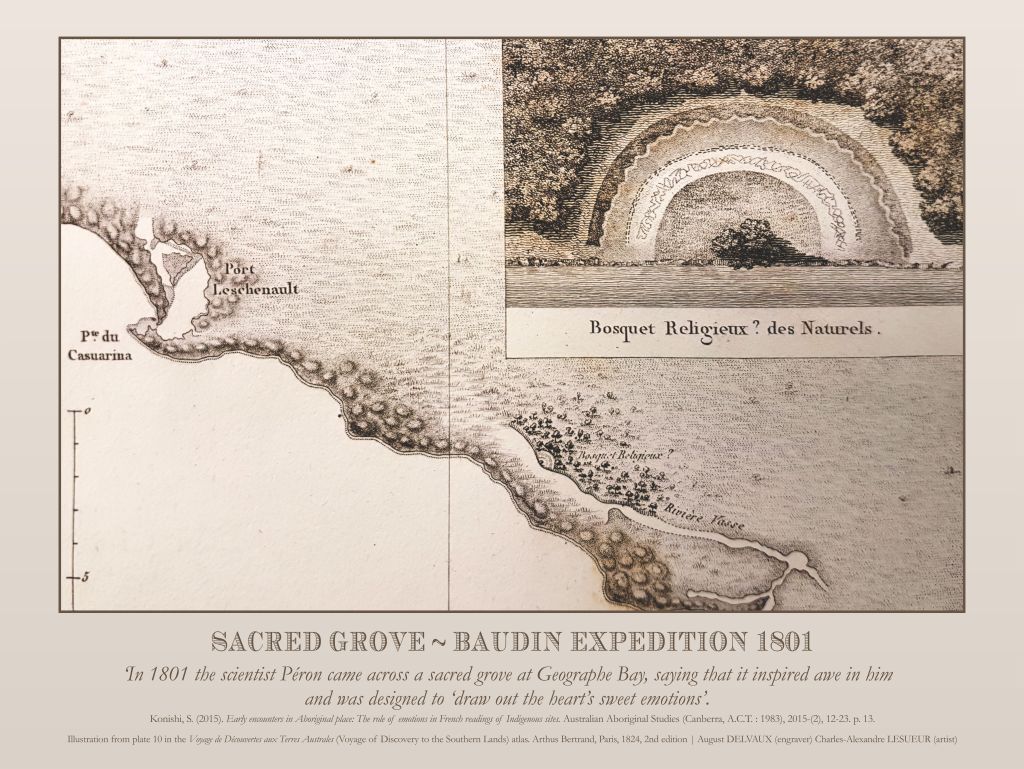

Previously in 1837 in June and July, settlers at Busselton massacred at least nine Wardandi people, after Gaywal and other family members killed and ate a calf.[3] In August 1837, the Bussell family took hostage a young Wardandi child from a family group near Capel, keeping the child until October. Eventually, Bun-ni along with a woman known as Mrs Woolgat, collected the child from Cattle Chosen and returned him to his family.[4] In December 1840, John Garrett Bussell went to the Leschenault district and arrested a Wardandi warrior called Nungundung, who had been resisting the settler invasion of his land, by spearing Wardandi youths who worked for settlers, and a settler shepherd called Henry Campbell.[5] Bussell sent Nungundung to Rottnest, and Wardandi people feared that he would be executed. This angered Gaywal, and several Wardandi people, including Bun-ni, warned Vasse settlers that there would be trouble.[6] Despite this tension, on 22 February 1841 Gaywal and twenty-two other Wardandi people agreed to help George Layman to thresh his crop at Wonnerup, in exchange for flour to make damper. That night, George Layman had an argument with Gaywal over the damper, and Gaywal speared and killed him.

On 23 February, John Garrett Bussell and Captain Molloy went in search of Bun-ni, as they had heard he wished to help hunt for Gaywal. They detained Bun-ni at Cattle Chosen, until ‘a conviction that he was true and zealous induced [them] to liberate him.’[7] Although Bun-ni appeared willing to help, he then took many actions to lead settlers astray in their search for Gaywal as the following report shows.

During the next week settlers conducted three punitive expeditions on Wardandi boodjar. Members of the 51st regiment, who were stationed at Wonnerup, and settlers at Wonnerup and the Vasse participated in all three expeditions.

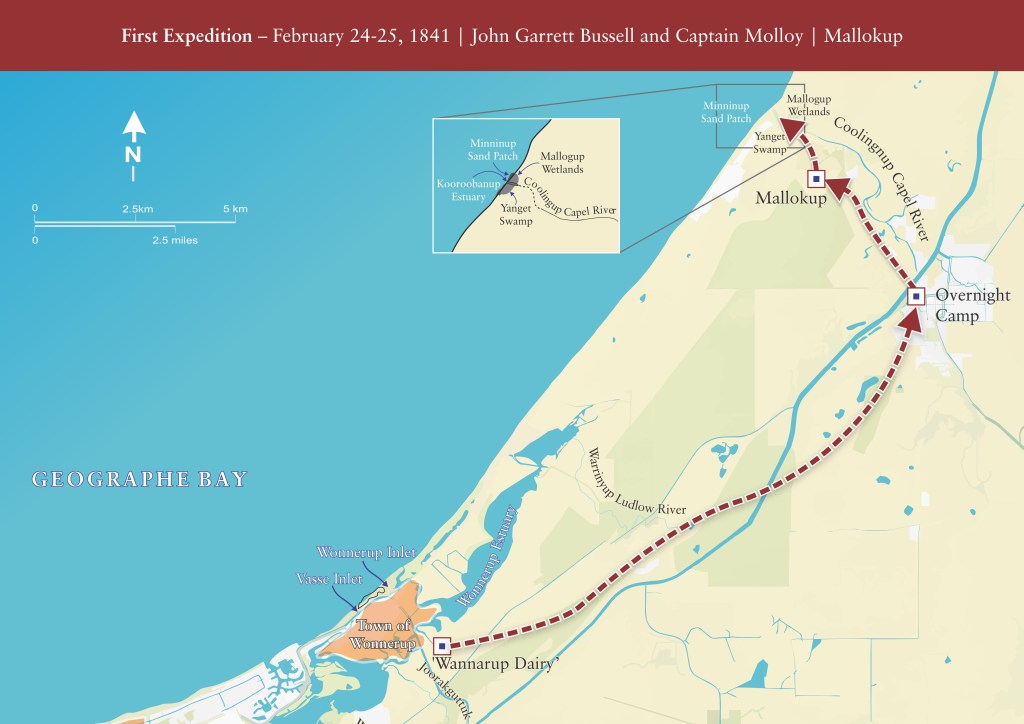

The first punitive expedition went out on 24 February 1841, led by John Garrett Bussell and Captain John Molloy, headed for Capel River and Mallokup. Bun-ni was designated a ‘special constable’ and guided this expedition.[8] As they searched for a group of Wardandi people that they suspected of hiding Gaywal, Bun-ni guided them through the swampy area at Mallokup, forcing the settlers to camp overnight without water. They camped overnight in sandhills near a group of Wardandi people, who they then attacked in a dawn raid. A report written by John Garrett Bussell and Captain John Molloy gives a disjointed description of a violent encounter, saying that five Wardandi people were killed.[9] This total number was already an understatement, as Fanny Bussell noted in her diary on 26 February that seven Wardandi people had been killed.[10]

A history of Western Australia from by Warren Bert Kimberly, gathered from settlers and Wardandi survivors in 1897 says that dozens of Wardandi people were killed, probably in this encounter.[11] An oral history from George Webb available in the State Library archives also relates how settlers pursued Wardandi people up to Minninup and killed many people.[12]

After this violent encounter, Captain Molloy and John Garrett Bussell took a group of surviving Wardandi people hostage, and headed the group back to Wonnerup.[13] They were disappointed that Gaywal was not among the dead, and annoyed at Bun-ni who was randomly firing his gun to warn other Wardandi people where the group was. So they ordered Bun-ni to go out and shoot Gaywal, threatening his family to ensure his compliance. Bun-ni went off for a while, and then caught up with the group as they arrived at Wonnerup that afternoon, saying that he had shot and killed Gaywal. John Garrett Bussell and Captain Molloy doubted this, deciding to send out a second punitive party to check. Their suspicions were correct, as Bun-ni had indeed not killed Gaywal. His intention appears to have been to protect and warn him instead.

When they arrived back at Wonnerup with the Wardandi hostages, John Garrett Bussell and Captain Molloy had received a message saying that Charles Symmons, the ‘Protector of Aborigines’ had arrived unexpectedly at Cattle Chosen, and they hurried off to meet him. The settlers at Busselton were angry that Symmons had arrived at such a volatile time. Symmons was simply undertaking a regular visit to the district, as part of his duties, but he was seen by the Vasse settlers as ‘a persecutor of the European’.[14]

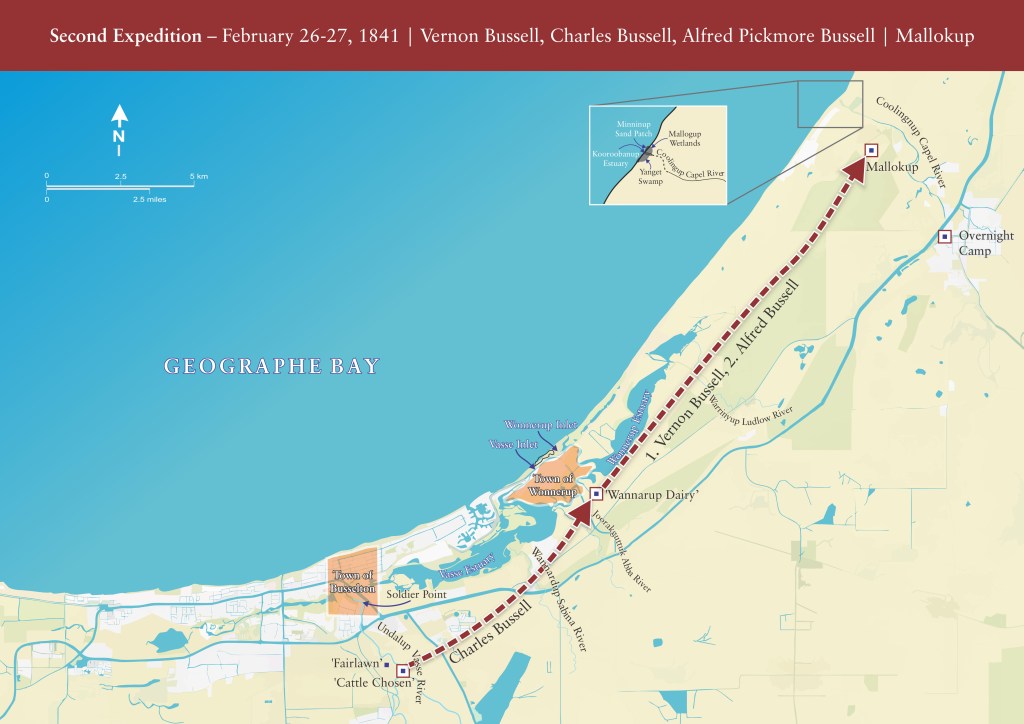

Vernon Bussell led the second punitive expedition, heading out from Wonnerup towards Mallokup on the evening of 26 February. Bun-ni was once again their guide. On the morning of 27 February they met up with a Wardandi group that pretended to be very afraid of Gaywal and offered to help find him. Bun-ni and the group of Wardandi people then led Vernon’s group astray for a day, getting them lost in the swamps at Mallokup. At the end of the day, Vernon and his companions took the Wardandi group hostage, sending for more ammunition and supplies. Due to a miscommunication, his brothers Alfred Pickmore and Charles Bussell thought he was surrounded by armed Wardandi warriors, rather than holding them hostage, and went out in two separate groups to help him. When Alfred’s group joined Vernon’s group, more Wardandi people were killed. Vernon Bussell reported that two Wardandi men were killed in this incident. Vernon’s punitive group and the hostages then went back to the Layman house at Wonnerup.[15]

During Vernon Bussell’s punitive foray, they met up with one of Gaywal’s wives, who told them that Gaywal had gone south, which was also not true. Acting on this information, John Garrett Bussell and Captain John Molloy led a third expedition from Cattle Chosen on 28 February, heading south in search of Gaywal. They returned on the 1 March, with John Garrett Bussell reporting that Bun-ni would not co-operate with them, so they had to abandon the search.[16]

The Vasse settlers then sent out a message saying that they would wait until Wardandi people gave Gaywal up to them. On 7 March, a Wardandi man nicknamed Crocodile sent a message to settlers, hoping to be forgiven for an offence against them and offered to give Gaywal up. A final expedition, led by Captain Molloy, John Garrett Bussell and Lieutenant Northey of the 51st regiment, headed out, guided by Crocodile. They found Gaywal at 3am on the morning of 8 March, and shot him as he rose up, reaching for a spear.[17]

This information, obtained from reports in the State Records Office and from other sources show that that Bun-ni, Gaywal’s wife, and the first and second group of Wardandi people, all took strong action to protect Gaywal and frustrate settlers in their search for him. The punitive activities by Vasse settlers depicted show similarities to the tactics they used in 1837: taking hostages, punishing the collective Wardandi group for an offence committed by one person, rather than simply arresting the offender, and under-reporting of the number of Wardandi people killed.

Due to this under-reporting, it is not possible to ascertain how many Wardandi people were killed in the violent events following George Layman’s death on 22 February 1841. The State Records Office reports, other colonial archives and Wardandi oral history do show that many Wardandi people were killed by settlers in these punitive actions. It is this event that we bear witness to today in the interest of truth-telling. Thank you for listening.

References

Bussell, John Garrett. “26 December 1840: Transcription of Letter to Peter Brown Col Sec Regarding the Arrest of Nugundung”. Battye Library, Shann papers, Acc 337A/788. State Library Western Australia.

“Diary of Elizabeth Capel Bussell April-December 1837”. Shann Papers, MN 586; ACC 337A/795, Battye Library. State Library of Western Australia.

“Diary of Frances Louisa Bussell (Junior) 1 April 1840 to 27 April 1841”. Bussell family papers MN586, ACC 337A/391, Battye Library. State Library of Western Australia. https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb6648830.

Kimberly, Warren Bert. History of West Australia: A Narrative of Her Past Together with Biographies of Her Leading Men. Melbourne: F.W. Niven and Co., 1897. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_West_Australia.

“List of ‘Native Constables’ July 1841.” Saturday 21 August 1841, page 4. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/643053.

Molloy, John, and John Garrett Bussell. “23 February 1841: Deposition of Mary Anne Rought” Acc 36, CSR Vol 100, SROWA.

———. “27 February 1841: Report on Death of George Layman” Acc 36, CSR Vol 101 folios 93-4, SROWA.

Molloy, John, John Garrett Bussell, Alfred Pickmore. Bussell, and Joseph Vernon Bussell. “10 March 1841: Report on Pursuit of Gayware”. Acc 36, CSR Vol 101 folio 99, SROWA.

“Cattle Chosen Massacre 1837.” Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930, University of Newcastle, 2017-2022, https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/detail.php?r=1035.

Shann, E. O. G. Cattle Chosen: The Story of the First Group Settlement in Western Australia, 1829 to 1841. Historical Reprint Series. Facsimile ed. ed. Nedlands, WA: University of Western Australia Press, 1978 reprint of 1926 edition.

Webb, George Edward. Interview by Ramona Johnson, 1989, Transcript, OH 2522/13. State Library of Western Australia.

[1] See John Molloy and John Garrett Bussell, “27 February 1841: Report on death of George Layman” Acc 36, CSR Vol 101 folios 93-4, SROWA. Also John Molloy et al., “10 March 1841: Report on pursuit of Gayware”, Acc 36, CSR Vol 101 folio 99, SROWA.

[2] “List of ‘Native Constables’ July 1841,” Saturday 21 August 1841, page 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/643053.

[3] “Cattle Chosen Massacre 1837,” Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930, University of Newcastle, 2017-2022, https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/detail.php?r=1035. There were two events, one just north of the Bussell family claim at Cattle Chosen, Busselton, and later on further east on the Sabina River.

[4] “Diary of Elizabeth Capel Bussell April-December 1837”, Shann Papers, MN 586; ACC 337A/795, Battye Library, 39, State Library of Western Australia. Bessie Bussell called her ‘Mrs Wolgood’ and she is possibly Wardandi man Woolgat’s wife. He is mentioned on page 45 of the diary.

[5] John Garrett Bussell, “26 December 1840: transcription of letter to Peter Brown Col Sec regarding the arrest of Nugundung”, Battye Library, Shann papers, Acc 337A/788, State Library Western Australia.

[6] John Molloy and John Garrett Bussell, “23 February 1841: Deposition of Mary Anne Rought” Acc 36, CSR Vol 100, SROWA.

[7] Molloy and Bussell, “27 February 1841: Report on death of George Layman”

[8] Molloy and Bussell, “27 February 1841: Report on death of George Layman”

[9] Molloy and Bussell, “27 February 1841: Report on death of George Layman”

[10] “Diary of Frances Louisa Bussell (Junior) 1 April 1840 to 27 April 1841”, Bussell family papers MN586, ACC 337A/391, Battye Library, See entry for 26 February 1841., State Library of Western Australia, https://encore.slwa.wa.gov.au/iii/encore/record/C__Rb6648830.

[11] Warren Bert Kimberly, History of West Australia: A Narrative of her Past Together with Biographies of Her Leading Men. (Melbourne: F.W. Niven and Co., 1897), 116. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_West_Australia.

[12] George Edward Webb, Interview by Ramona Johnson, 1989, transcript, OH 2522/13, 29, State Library of Western Australia.

[13] Molloy and Bussell, “27 February 1841: Report on death of George Layman”

[14] E. O. G. Shann, Cattle Chosen: the Story of the First Group Settlement in Western Australia, 1829 to 1841, Facsimile ed. ed., Historical reprint series., (Nedlands, WA: University of Western Australia Press, 1978 reprint of 1926 edition), 118.

[15] Molloy et al., “10 March 1841: Report on pursuit of Gayware”.

[16] Molloy et al., “10 March 1841: Report on pursuit of Gayware”.

[17] Molloy et al., “10 March 1841: Report on pursuit of Gayware”.